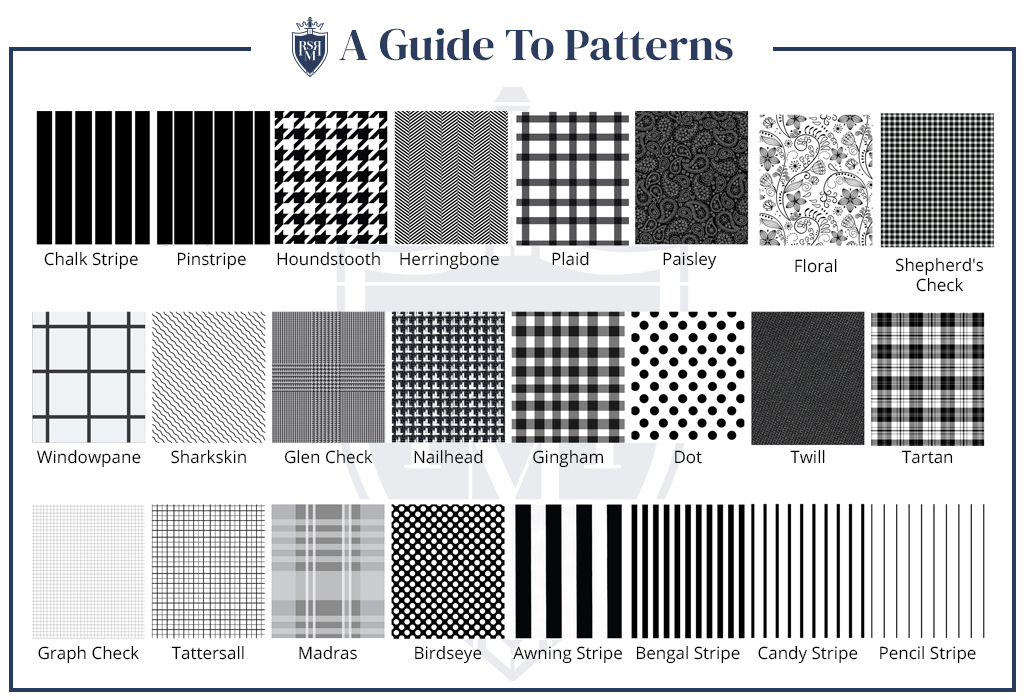

So far we've talked about color and pattern.

These are the easiest characteristics to identify in a suit — apart from the occasional color-blind fellow, most men can pick out the difference between a navy blue suit with pinstripes and a deep forest green suit with no pattern.

But what happens when the navy blue suit is made from a thin, stiff blend of fibers while the green one is made from very fine threads of thick, rich wool?

The texture of the fabric ends up making more of a difference than you might think, both in terms of how it looks and in how comfortable it is to wear.

We'll talk about weaves, which can also affect the physical texture, in another section.

Here we'll just focus on specific aspects of the thread and cloth that can change the texture of your suit:

Base Material

We have a whole section on the materials you can make a suit out of! Here's the one-sentence summary on each material and the textures they tend toward:

- Wool – Versatile and durable; can range from silky-smooth to coarse and wiry; 100% wool gives a good, clean drape over your body. Soft or coarse and somewhat fuzzy.

- Cotton – Light and breathable; lacks the weight and smooth drape of wool; surface tends to feel a bit “harder” or stiffer than wool. Solid and unvaried texture.

- Linen – Very light with an almost gauzy feel; wrinkles easily and tends to billow instead of draping. Gauzy surface with a discernable weave.

- Silk – High sheen and amazingly smooth to the touch; wrinkles easily; won't drape unless it has wool or something else underneath to give it weight. Smooth almost to the point of slickness.

- Exotic Animal Hairs – Can vary widely, but mostly behave like a normal wool with a smoother surface; can be lighter and more billowing than sheep's wool. Luxuriously soft and somewhat fuzzy.

- Artificial Fibers – Durable and solid; often slick or plastic-like. Stiff and smooth.

Thread Type

The way the thread itself is spun out of the raw wool effects the texture of your suit.

- Worsted threads use wool (or another material) in which the fibers have been combed to all lie parallel. They are then twisted together to make a hard, strong yarn with a mostly smooth surface. Cloth from worsted threads has a matte finish that's firm and smooth to the touch.

- Woolen (also spelled woollen) yarns are made from wool that has been “carded” with a sharp-toothed brush rather than combed. The resulting threads are softer and can have a natural fuzziness to them. Flannels and tweed are made from woolen threads.

Some suitings will be made from woolen threads and then combed again on the surface of the cloth, creating a soft finish of stray threads that make the suit fuzzier to the touch.

Yarn Number

Yarn number is a measurement used in wool suits to describe the “fineness” of the wool. The origin of the measurement is somewhat esoteric: it describes the number of 560-yard spools of thread a spinner could get out of one pound of the raw wool. The higher the number, the finer the spinner is spinning the thread, and therefore the smoother and finer the surface of the finished wool feels.

What that means in practical terms is that a higher number means a lighter, smoother wool, while lower numbers have a coarser and heavier-feeling surface because each thread contains more wool woven less tightly.

There are no official categories, and the textile industry has notoriously imprecise measuring standards in some regions of the world, but there's loose consensus among finer tailors regarding the role of specific yarn numbers:

- 60s and below are thick, coarse cloths made from big threads. Most suits made from cloth like this won't bother listing a yarn number, since it isn't a real selling point for this kind of fabric. Tweeds can often be this low.

- 70s – 90s are a typical range for custom suitings. Worsted yarns in this range make smooth, elegant suits that are sturdy enough to hold up to daily wear and reasonably regular cleaning. They have enough weight to drape firmly but can still be made very smooth and pleasant to the touch.

- 100s – 120s are “supers,” a word automatically applied to wool cloths with a three-digit yarn number. These have a very smooth surface and are much lighter than conventional business suits. “Tropical wools” are often supers, as are luxury suits for men who like the silky feeling.

- 120s and up are the extremely fine upper range of wool suits. Most tailors would consider these too finicky for daily wear — prone to wrinkling and difficult to care for — but there are customers out there creating demand for suits with yarn numbers ranging up to the 200s. They're lovely to touch, but not very practical.

Fabric Weight

Raw fabrics also often list the weight of a single bolt yard. This is often influenced by the yarn number but is a separate measurement, and mostly helps you determine how warm a wool will be and how firmly it's going to drape over your frame.

- Under 10 oz. is usually considered a “tropical” wool, made with fine threads and a loose weave to create a breathable fabric. They don't have the smooth drape of a heavier wool, but are a mercy to wear in hot weather.

- 10 -14 oz. cloths cover the “three-season” range of suitings. These are mostly worsteds and lighter flannels made to be worn most of the year round in temperate climates. They sit nicely on the body and provide a bit of warmth.

- 14 oz. and up are heavier cloths, usually tweed or flannel, meant for warmth and extra weight. They drape quite heavily on the body and can add a bit of padding to your frame as well.

Combining all these terms at once can sound dizzyingly technical — it's hard to hear a tailor rattle off something like “a 12 oz. worsted flannel in the 90s” and immdiately come up with a good idea of what that suit would feel like. Instead, we recommend thinking about the finished texture you want and then searching out the right cloth to achieve that:

How smooth do you want the suit to feel?

A silky-smooth surface will need a fine, high-yarn-number fabric, usually made from worsted threads.

If you prefer a soft and slightly fuzzy surface a mid-weight cloth in the normal yarn number range (70s to 90s) will serve you fine.

For a rough country jacket you're more likely looking at low yarn numbers and a loose woolen thread.

How firm of a drape do you want?

A good “drape” means the suit is following your body's lines and staying close in even when unbuttoned. The lighter the fabric the shakier your drape becomes — very fine and light wools tend to billow out rather than staying smooth like the heavier cloths.

How hard will you be using this suit?

Extra-fine wools and more exotic materials don't hold up well to regular wear. A daily work suit that you're expecting to wear once a week or more will need to be made out of a reasonably low yarn number wool rather than one of the three-digit “supers.”

A fancier suit that you only plan on wearing for a few hours at a time during occasional social events can be made silky-fine and lightweight — just beware that it will be prone to wrinkling if not stored properly, and may start to lose its luster after a few years if you're having it dry-cleaned regularly.

Between the considerations of surface feel, drape, and practical use, it should be easy for you to narrow down the perfect material for your suit!