Add up all the things we've discussed — raw material, weave, color, pattern; texture — and you get a fabric. A specific fabric: a bolt of cloth that you can point to and say “I'd like that one please.”

Not all suits are business suits. Many good wool cloths stocked by tailors are meant for fashionable, casual, or social wear rather than business.

Since most custom suit buyers, particularly first-time customers, are looking for business wear, we thought a short overview of the most common fabrics that are specifically business-appropriate would be worthwhile.

Charcoal or Navy Worsted Wool

The most traditional business suit out there is made of worsted wool in either dark charcoal gray or dark navy blue. The cloth is sturdy, matte-colored, and smooth-textured:

- Color – Charcoal gray or navy blue only, the deepest versions — just a few shades from black.

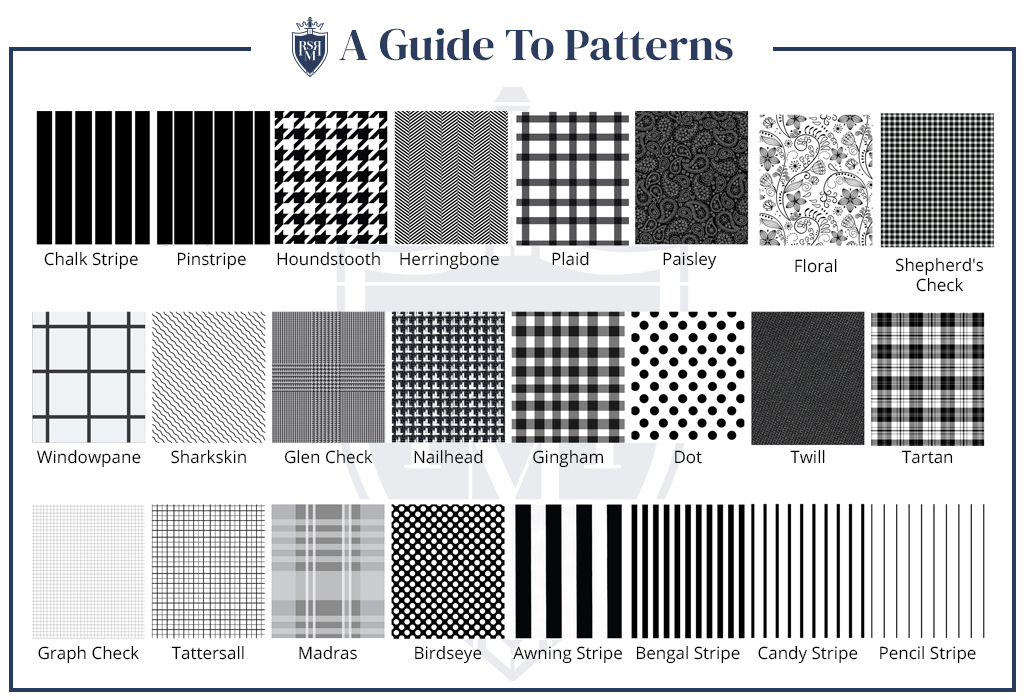

- Pattern – Solid, or white pinstripes (true pinstripes, only a thread's width broad).

- Thread – Worsted thread of moderate fineness. Yarn count in the 70s-90s, or the low 100s for a more expensive, slightly less sturdy suit.

- Weave – Usually a twill weave with the smooth side outward, or else a very tight plain weave. Either way the facing is even and untextured.

- Weight – Typically “three-season” wool, between 10-14 oz.

- Formality – Highest level of business dress. Appropriate anywhere up to and including “black tie optional.” Sometimes too stark for casual business settings.

Gray Flannel

In the middle of the 20th century this was the standard suit for well-to-do businessmen, so universal it gave the title to the novel and film The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. It remains a business staple, though not as formal as dark worsted wool.

- Color – Medium or light gray; basically anything lighter than charcoal is fair game.

- Pattern – Solid medium-gray, or else faint gray-on-gray check patterns in very slightly differing colors of thread.

- Thread – Short-staple wool thread. Worsted and woolen yarns are both used to make flannel cloth; woolen yarns give a softer, fuzzier finished texture than worsted. Yarn count can vary somewhat widely, from the 60s to the 90s.

- Weave – Twill or plain weaves; either one will be “napped” — brushed across the surface with a sharp-toothed brush to make the surface of the threads softer and fuzzier.

- Weight – Usually three-season wool, between 10-14 oz.

- Formality – Basic business wear. Lacks the high formality of charcoal/navy worsted suits — too casual for an important presentation or a board meeting, but good for day-to-day office use.

Glen Check

Also called Prince of Wales check, or occasionally by its full name Glenurquhart check/plaid. Glen checks are not a formal clan tartan, and are not limited to any particular color scheme; rather, the name refers to the specific pattern of small and large checks woven into the fabric. It remains a popular business suiting, though less formal than solid-colored wool suits.

- Color – Varies, with business suits usually opting for gray-and-black, gray-and-blue, or blue-and-blue versions. Sometimes a single line of a brighter color such as red or lavender will run through the pattern at broad intervals.

- Pattern – Distinctive and specific set of checks. Because the pattern is woven rather than dyed the lines will have a slight unevenness around the edges when viewed closely. Considered more business-formal than most check patterns.

- Thread – Traditionally woolen yarn. Low yarn count, usually 60s – 80s for a sturdy, thick-textured fabric.

- Weave – A specific twill weave that creates the pattern, as well as giving the surface light diagonal ridges that produce a textured feel.

- Weight – Can vary widely. The pattern is traditionally associated with gamekeepers and hunters, so a heavier weight for outdoor use is common, but business suits are often made lighter.

- Formality – The more casual end of business suits. In a very formal office it might be Friday-only wear, while in a more relaxed suit-and-tie business it could be serviceable day-to-day wear, acceptable anywhere outside of a formal presentation or important meeting.

Herringbone Worsted

A slightly more casual variant on the basic worsted wool suit, herringbone-woven business suits are often in lighter or more casual colors as well. They can range from quite formal to more casual depending on how pronounced the weave is and what the color is. It is important to note that a herringbone tweed is a different creature and not a business suit, unless you happen to be an academic.

- Color – Typically a light or medium gray, brown, or blue, though darker colors offer a bit more formality. If all the threads are the same color the weave is subtler and looks solid from a distance; if the warp and weft are slightly different colors the effect becomes more pronounced.

- Pattern – None apart from that of the weave itself.

- Thread – Smooth worsted threads. Finer threads make a particularly elegant herringbone suit, so yarn numbers in the 80s on up through the Super 120s are not uncommon. Anything finer is impractical for all-day business wear.

- Weave – Herringbone, the distinctive pattern of alternating V-shapes. A narrower V is more formal.

- Weight – Varies, usually in proportion to the fineness of the yarn — a Super 120 herringbone suit might weigh in at about 8 oz., while one in the 80s could be a heavy winter wool of 16 oz.

- Formality – Variable. In dark colors with a subtle weave and fine threads, it's a minor variation on the traditional charcoal/navy worsted suit. In brown or lighter grays with a more pronounced weave it's a casual suit similar in formality to the Glen check.

Birdseye/Nailhead/Barleycorn

Three similar suitings all defined by their weave, these can be business-appropriate when done in darker colors, usually in blues and grays. Each one requires threads of two different colors to produce their distinctive effect. At a distance the eye blends the colors into a more solid appearance. This works best when the colors are closely matched, i.e. a dark gray and a slightly lighter gray.

- Color – Gray, blue, or brown. Because of the blending effect the color always appears somewhere between the two threads used.

- Pattern – None apart from the weave itself.

- Thread – Thick worsted threads work best, though coarser woolens are not unheard-of. The patterns show best if the threads are thick and sturdy, so yarn numbers are usually in the 70s or 80s.

- Weave – Each of the three is a different construction, but the effect is of a small, regular pattern in the lighter color repeated against the background of the darker. Birdseye is the smallest and looks like tiny regular dots, while nailhead is a larger variation of the same and barleycorn creates tiny repeating triangles instead of circles.

- Weight – Often on the heavier end of three-season weights, around 14 oz., but it can vary. Birdseye is occasionally used in much lighter tropical-weight suitings.

- Formality – Relaxed business appropriate. Birdseye is smaller and subtler, and therefore more formal, while nailhead and barleycorn would not be appropriate in any kind of formal meeting or presentation, and make good Friday suits instead.

Striped Seersucker

Something of a rarity these days, striped seersucker bears mentioning both because of its traditional association with government and because of a resurgence among younger wearers. Men of influence in the American South have long worn seersucker in the summer, and the United States Senate honors the tradition with a “Seersucker Thursday” in June. For civil servants it can be business wear during the summer, while for most other businessmen it is best reserved for a weekend suit.

- Color – Solid white or white with another color of stripe, usually blue, green, or light gray.

- Pattern – Solid white or “candystripe” — alternating stripes of equal width in white and one color. Plaid and gingham seersucker suits do exist, but are emphatically not business wear.

- Thread – Light cotton, usually not an extra-fine or extra long-staple. Seersucker is sometimes made with varying widths of thread to enhance the “crinkle” effect.

- Weave – Very specific weave with a bumpy, puckered texture. Light and cool in the summer, allowing extra airflow.

- Weight – Quite light. Rarely more than 8 oz. to the yard.

- Formality – Relaxed and not usually business-appropriate, outside of government settings and casual offices that still mandate suit-and-tie wear. Traditionally not worn between Labor Day in the fall and Memorial Day in the early summer.

These are hardly the only options out there, but they are a good introduction to business suit fabrics. The most important take-away, apart from some good starting ideas, might be how we put them all together: each individual “fabric” is the product of all the different elements we've talked about throughout this guide.

Once you start to think of fabrics in terms of color, pattern, material, weave, and weight, you're in a pretty good place to start doing business with tailors. And, of course, to start exploring the many suit and jacket fabrics out there suitable for more casual wear that lie beyond the scope of “business fabrics”…